As I mentioned last week, I was able to interview a number of extremely interesting people from very diverse backgrounds. Although each person is fascinating in their own right, my interview with a young couple in their late 30s was by far the most thought provoking. Their perspective on SMA was much like those who have lived here for 30+ years, with a few significant exceptions. Their comments are also revealing about the shifting nature of "community" and local identity in SMA.

The couple I interviewed, who I will identify here by the pseudonyms "Pete" and "Tonya" are former small business owners who decided early in life that they wanted to retire by the time they were 40 (or in their early 40s). With this goal in mind, they worked hard with their businesses and consistently lived below their means in the U.S. (living in a small condo instead of buying a house, driving 10 year-old plus cars) so that they could reach this goal. For years they were moving toward the goal, and each year they would visit SMA because Tonya's father had retired here. The plan was to eventually live in an apartment next to Tonya's father.

Then Tonya's father suddenly died.

Like many people who have suffered a major loss, Pete and Tonya decided that the time to retire was now. They sold their businesses, invested heavily and fortuitously in the stock market (they got out just before the IT bust), sold their assets and bought a pick-up truck and a 30-foot RV and started their retirement. He was 32, she was 30.

Their lives have not been limited to SMA, and their commitment to living her and only here is not nearly as strong as some of the older retirees who live here. They don't have permanent visas to live in Mexico (which is very common here), so they must cross the border into the U.S. every six months to live here legally and to keep their vehicle here. Their extended families are still in the U.S., and although they get regular visitors here, they still go back to the U.S. for 1-2 months every year.

Tonya majored in Spanish in college, so she is fluent in Spanish. Pete learned to speak Spanish here. Both report that they have about the same number of friends who are Mexican and American/Canadian; although they also say they are not "social" and prefer to keep to themselves. In this respect, they differ markedly from other expatriates from the U.S. and Canada. They did not come here to find a community, but they just like living the way they want to without any particular obligations to anyone but each other, and living in a camper in Mexico allows them to do that.

Like many of the "old timers" in SMA (those who have been here 20 years or more, Pete and Tonya aren't overly pleased with the mass in-migration of extremely wealthy North Americans. They have many Mexican friends here who live in and around the jardín, and many of them are selling out because Americans can offer them outrageous prices for their properties. Their major concern is that the center of town, which is by far the heart of any Mexican community, will soon be a Mexican-free zone. No one is being pushed out or gentrified out of his or her neighborhood, however. Mexicans generally own their properties outright (mortgage loans are still relatively uncommon here) and taxes are extremely low. But the pressure to sell and make a profit that might equal 4-5 times a typical Mexican lifetime salary is enough to encourage Mexicans to sell their properties.

This blog features my research on Northern Virginia's dynamic and diverse communities.

Sunday, July 30, 2006

The Unchanging Nature of Men

As promised, I'm going to give an overview of the issues that I encountered during the week. Several of you have written asking about the "Unchanging Nature of Men" group luncheon of last Wednesday. Well, this is a much what we would call a chiste (joke) in Mexico. The "platform"of the group reads:

Obviously, there is no serious content here, just a bit of male posturing. I honestly think I was invited to join the group because we've had some good conversations in the jardín, and also because the "king" wanted to see my reaction to the platform. What was my reaction? Well, let's just say I'm too old and too smart to walk into that one. I didn't offer a reaction (I am, after all, a visitor here), but I may at some point offer an analysis of the platform, which was written by retirement-age men and focuses on bladder function. On second thought, I won't offer an analysis. This is way too straightforward.

The Unchanging men's group was created to celebrate the unchanging nature of men. We as a group do not flower or evolve as much as women do. We tend to find things that we like and stick to them, Ex-wives included. We like to think of this as being stable and consistent.The Unchanging men's group supports the following planks in our platform. They are:

- The destruction of all toilet seat covers that can cause bladder distress and extreme shock to men when the seat falls down, or back problems trying to hold the toilet seat up.

- The continued complete control of all remote controls by men.

- The Encouraging of women to lift the toilet seat when they are finished.

- The halting of all garage conversations unless they (garages) are converted into a micro brewery.

- The right for men to scream and run out of the door without penalty when his mate asks if she looks fat or if she has gained weight.

New ideas are considered in the Jardín and will be discussed and possibly added to the platform .

Thanks for coming and enjoy your lunch.

Obviously, there is no serious content here, just a bit of male posturing. I honestly think I was invited to join the group because we've had some good conversations in the jardín, and also because the "king" wanted to see my reaction to the platform. What was my reaction? Well, let's just say I'm too old and too smart to walk into that one. I didn't offer a reaction (I am, after all, a visitor here), but I may at some point offer an analysis of the platform, which was written by retirement-age men and focuses on bladder function. On second thought, I won't offer an analysis. This is way too straightforward.

Saturday, July 29, 2006

The week in pictures

Much to my surprise, most expatriate retirees like to take the weekend off and, in general, are not available for interviews. For the next few days I'll be filling in the blanks from the week, and here are some photos of our week in the field:

At our summer camp school. The kids' are in a bilingual institute for the next few weeks. They have formal language instruction, fieldtrips, cooking and crafts. Here they're posed with a monjiganga, one of the large puppets that are commonly paraded in fiestas in Mexico. It was made a one of the craft projects by students in the school.

Ken was facinated by the road construction techniques in use here that essentially reproduce the roads as they have been here for over 400 years. Most of the streets are cobblestone, but along Ancha de San Antonio they use flat pavers.

Our neighbor's dog, Cerveza.

The Parrochia (Parish Center) on Wednesday evening after Gringo Happy Hour. This was taken right before it started to pour (about 8:15 PM).

The Parrochia (Parish Center) on Wednesday evening after Gringo Happy Hour. This was taken right before it started to pour (about 8:15 PM).

Making contacts. Walking on our way to camp, we stop to pet our neighbor's Border Collies.

The last day of camp. Every week on Fridays the camp throws a party with Tunas, tamales, and lots of good cheer.

The last day of camp. Every week on Fridays the camp throws a party with Tunas, tamales, and lots of good cheer.

At our summer camp school. The kids' are in a bilingual institute for the next few weeks. They have formal language instruction, fieldtrips, cooking and crafts. Here they're posed with a monjiganga, one of the large puppets that are commonly paraded in fiestas in Mexico. It was made a one of the craft projects by students in the school.

Ken was facinated by the road construction techniques in use here that essentially reproduce the roads as they have been here for over 400 years. Most of the streets are cobblestone, but along Ancha de San Antonio they use flat pavers.

Our neighbor's dog, Cerveza.

The Parrochia (Parish Center) on Wednesday evening after Gringo Happy Hour. This was taken right before it started to pour (about 8:15 PM).

The Parrochia (Parish Center) on Wednesday evening after Gringo Happy Hour. This was taken right before it started to pour (about 8:15 PM).

Making contacts. Walking on our way to camp, we stop to pet our neighbor's Border Collies.

The last day of camp. Every week on Fridays the camp throws a party with Tunas, tamales, and lots of good cheer.

The last day of camp. Every week on Fridays the camp throws a party with Tunas, tamales, and lots of good cheer.

Friday, July 28, 2006

The artists' colony

A great deal has transpired in the last 24 hours. I've had interviews with a centenarian, a world renouned artist, thirty-something retirees, and had lunch with the "Unchanging Nature of Men" group, a true cross section of the San Miguel de Allende (SMA) expatriate community. Although I promise highlights form each, I'm going to talk about SMA's history as an artists' colony from the mid-1940s to the present. This morning I had the pleasure of talking with Leonard Brooks, perhaps the best-known artist that SMA has produced (or nurtured).

A great deal has transpired in the last 24 hours. I've had interviews with a centenarian, a world renouned artist, thirty-something retirees, and had lunch with the "Unchanging Nature of Men" group, a true cross section of the San Miguel de Allende (SMA) expatriate community. Although I promise highlights form each, I'm going to talk about SMA's history as an artists' colony from the mid-1940s to the present. This morning I had the pleasure of talking with Leonard Brooks, perhaps the best-known artist that SMA has produced (or nurtured).I met with Leonard Brooks at his home this morning (photo of the grounds below) at the suggestion of another informant. I knew of Leonard and Reva Brooks, of course, because of Jack Virtue's biography of their lives and work in SMA. I would have never dreamed of calling on Mr. Brooks, however, simply because he seemed too remote for a project like my own. However, I did call yesterday afternoon. His sister-in-law answered the phone (she's a delightful woman) and made an appointment to visit this morning.

Mr. Brooks is nearly 95 years old. He lives in a house that is about half a mile from the central jardín, a lovely walled complex of about an acre with two structures: his studio and a lovely home and garden. Like so many of the first generation San Miguelian expatriates, he looks remarkably fit and has an incredible memory. He still works everyday, has written two books in the last year, and is planning an exhibit of his watercolor collection for later this year in Mexico City.

Mr. Brooks is nearly 95 years old. He lives in a house that is about half a mile from the central jardín, a lovely walled complex of about an acre with two structures: his studio and a lovely home and garden. Like so many of the first generation San Miguelian expatriates, he looks remarkably fit and has an incredible memory. He still works everyday, has written two books in the last year, and is planning an exhibit of his watercolor collection for later this year in Mexico City.Leonard Brooks was an early arrival to SMA. He came shortly after he was discharged from the service (World War II). He was looking for a place to "get away from the war" and concentrate on his work. When he and his wife Riva found SMA "by accident" in 1947, there were some 15 American or Canadian expatriates living here. They had come, he recalled, because they were affected by the war and felt unwelcome in their home societies. Like the other GIs, Brooks lived on his army pension and found a small house on a hill overlooking SMA. There was no water, no electricity and no gas service to the house, but he nevertheless found it the perfect place to paint.

His house is overflowing with his artwork and photographs for which his late wife, Reva Brooks, is well known. As we talked about the charming nature of this community, Brooks noted that like his peers, he is not overly enthusiastic about the transformation SMA has undergone in the last decade. The wealthy investors have made the community unaffordable for upcoming artists, and the proliferation of art galleries in the city makes it possible for mediocre artists to join exhibit in a town where once only the most-established professional artists were featured.

Brooks stands apart from other people I've talked to here in that he sees himself, and his peers, as responsible for the changes in SMA. When I asked him why SMA transformed into place where the very wealthy seek to buy seasonal homes he said, "Well, it's our fault, the artists and painters. I painted San Miguel, and we all wrote about how wonderful it was here. In a sense, we've sullied our own nest." At the same time, he is not nostalgic for the SMA of the past, because he recognizes that all places change and transform. He mentioned a former mining town about an hour's drive from here that is now attracting young artists. Like SMA, it has an old-world charm, but not the mystique of this community.

Overall, I found Leonard Brooks to be kind and thoughtful, and I appreciated my time with him very much. Right before I left, he showed me around the house and his studio, where he rarely paints now. Instead his living room has become his studio, and there was a beautiful painting of San Miguel as he remembers it from the late 1940s. It is sparse painting showing several young men and their burros moving through the streets as evening falls. There are no cars, no large homes, and no crowded streets. It is a peaceful memory of this community as it once was, and was magnificent to behold.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Much ado about Nothing

I was disappointed (but not surprised) to read that the House is currently "debating" a bill to make English the official language of the U.S. Rather than addressing the issue here, that is, to provide more English classes for those who want to learn to speakn English, our leaders have decided to debate an issue that will not change anything.

I've been working here in San Miguel de Allende (SMA) for two weeks now. The American popultion here, even those who have lived her for over 20 years, is ovewhelmingly monolingual. It's not that many of these folks don't want to speak the language of the Mexican Republic, but many of them arrived in their 60s and 70s, and found it difficult, or in some cases impossible, to learn a second language in their later years.

In the U.S., there are few immigrants who don't understand that speaking English translates into better jobs, better pay, and more opportunities. They also know that there are rarely enough ESL classes to meet the demand of the rapidly growing immigrant population. Sure, there are people who come to the U.S. who will never learn to speak English. Having worked with Mexican immigrants in the U.S. for over a decade, most often these are older immigrants or women who don't work outside the home. Like their immigrant predecessors of a generation ago, they want their children to learn English, and in many cases, would like to learn to speak English themselves.

By the way, although the American population here is relatively small (estimated between 5-8% of the overall population), the businesses here all have bilingual signage. They do for precisely the same reason businesses and municipalities in the U.S. have translators and bilingual signage: it's good for business.

If it is indeed a national priority for America's immigrants to learn English, why not create a volunteer corp to pair Americans with immigrants so they can practice speaking English? Or even funding ESL programs so that the number of courses can meet the growing demand?

I've been working here in San Miguel de Allende (SMA) for two weeks now. The American popultion here, even those who have lived her for over 20 years, is ovewhelmingly monolingual. It's not that many of these folks don't want to speak the language of the Mexican Republic, but many of them arrived in their 60s and 70s, and found it difficult, or in some cases impossible, to learn a second language in their later years.

In the U.S., there are few immigrants who don't understand that speaking English translates into better jobs, better pay, and more opportunities. They also know that there are rarely enough ESL classes to meet the demand of the rapidly growing immigrant population. Sure, there are people who come to the U.S. who will never learn to speak English. Having worked with Mexican immigrants in the U.S. for over a decade, most often these are older immigrants or women who don't work outside the home. Like their immigrant predecessors of a generation ago, they want their children to learn English, and in many cases, would like to learn to speak English themselves.

By the way, although the American population here is relatively small (estimated between 5-8% of the overall population), the businesses here all have bilingual signage. They do for precisely the same reason businesses and municipalities in the U.S. have translators and bilingual signage: it's good for business.

If it is indeed a national priority for America's immigrants to learn English, why not create a volunteer corp to pair Americans with immigrants so they can practice speaking English? Or even funding ESL programs so that the number of courses can meet the growing demand?

Gringo Happy Hour

You never know what you're going to find here. Last night Ken, the kids (yes, they went too) and I went to Gringo Happy hour. Bill (a.k.a. "the King of the Jardín") invited us last week, so we decided to check it out. The bar, Los Milagros, is a spacious place that was wall-to-wall gringo. The photo above of Bebe and her mommy Jo was taken when we arrived. I was sorry the photo didn't turn out as well as I hoped, because they both looked quite lovely otherwise (Jo and Bebe always dress alike).

Over the course of the 6-8 PM happy hour, a two-man band sang gringo tunes (mainly country and western) and the some 100 people socialized from table to table. The main bar was full, there was also a back room with a pool table where the kids were about to hang out and play billiards (which is what my kids did).

Everyone was very friendly, and it was but one example of the events here to create a sense of community. The King of the Jardín pulled Ken and me aside during the evening and suggestethatht we move here, because we fit in so well with the "native" crowd. That is a fieldwork coup, let me tell you.

Today I've been invited to the "Unchanging Nature of Man" luncheon. I'm not sure what that will entail, but I'll be detailing it here. And Ken has been invited to join the guys for lunch during the week (a group of Dallas men get together Monday through Friday for lunch). We were both actually invited to all of the events, but someone has to take care of the kids, so we plan to rotate.

I was able to finish my interview with Julia yesterday. The Soundstudio software worked great and the computer recorded at a pretty high quality, so until my sister and mom arrive with my back-up equipment, I'm able to plug along as well.

More later this afternoon...

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Good dog

Yesterday was a bad day, but today will be better. Ken and I spent several hours last night refitting our laptops with recording software so that I can now use either to tape interviews. My sister and mother are coming to visit early next week and I've asked them to bring a new digital recorder. So, it looks like I'm back in business.

This morning while I was walking the kids to camp, I stopped to talk to a woman with two border collies. I miss my own dog, so I like to chat up dog owners I meet. In general, it's not a good idea to pet or feed stray dogs in Mexico. Most tourists who are bit by dogs (and subsequently have to be treated for rabies) initiate the contact with the dog. But San Miguel de Allende is a different place for dogs. The American community started an SPCA here, and there are very few stray dogs on the streets. Nevertheless, I don't touch a dog, on or off the leash, until I've established that it has been vacinated.

The border collie woman has lived here for 5 years full-time, before that she did six months in Texas (her home) and six months here. Although she hasn't been her very long, she's very well connected with the old timers, and is going to help set up introductions with her circle of friends.

I'm so glad I stopped to pet her dogs.

Based on my conversation with Julia yesterday, I see there is a pretty big divide not so much between Americans and Mexicans (there relationships seem to have been pretty consistent throughout the years), but between the first wave of expatriates and the newer group (those who have arrived in the last 5 years). It appears that as the American community has grown, it has made it possible for people who aren't ready to "make the plunge" full-time to come here for several months a year to live.

While this is a typical "snow bird" pattern that is common in the U.S., Julia said it has killed the sense of community among ex-pats in SMA. The reason? The first wave of settlers here were a group of highly talented, highly educated retirees who were not ready to give up on work. They were volunteers and wanted to give back to the municipio (basically a county) of San Miguel de Allende, which includes the city proper and the rural "ranchos" in the outlying area. In the first 30 years of expatriate settlement, there was a flurry of charitable activity, and today there are over 200 charitable organizations in SMA. Some are based on basic needs, for instance Feed the Hungry is a program that raises money to feed school children two times a day for 10 and a half months a years (the school year). The Biblioteca Municipal (Public Library) is an amazing bilingual library that is one of the biggest in Mexico. There are fine arts organizations, educational scholarship associations, it goes on and on. Julia said that the part-timers are not as invested in the community as the full-time residents have been, and the charities have suffered as a result. There are fewer people to do the day-to-day work, although ironically, the community has become much wealthier with the infusion of ever wealthier gringos.

When is started off here, I thought my primary research objective (long-term) would be to examine the relationships between gringos and Mexicans. This division within the expatriate community is a new layer that I hadn't expected, and one that I plan to explore more fully during this research trip.

This morning while I was walking the kids to camp, I stopped to talk to a woman with two border collies. I miss my own dog, so I like to chat up dog owners I meet. In general, it's not a good idea to pet or feed stray dogs in Mexico. Most tourists who are bit by dogs (and subsequently have to be treated for rabies) initiate the contact with the dog. But San Miguel de Allende is a different place for dogs. The American community started an SPCA here, and there are very few stray dogs on the streets. Nevertheless, I don't touch a dog, on or off the leash, until I've established that it has been vacinated.

The border collie woman has lived here for 5 years full-time, before that she did six months in Texas (her home) and six months here. Although she hasn't been her very long, she's very well connected with the old timers, and is going to help set up introductions with her circle of friends.

I'm so glad I stopped to pet her dogs.

Based on my conversation with Julia yesterday, I see there is a pretty big divide not so much between Americans and Mexicans (there relationships seem to have been pretty consistent throughout the years), but between the first wave of expatriates and the newer group (those who have arrived in the last 5 years). It appears that as the American community has grown, it has made it possible for people who aren't ready to "make the plunge" full-time to come here for several months a year to live.

While this is a typical "snow bird" pattern that is common in the U.S., Julia said it has killed the sense of community among ex-pats in SMA. The reason? The first wave of settlers here were a group of highly talented, highly educated retirees who were not ready to give up on work. They were volunteers and wanted to give back to the municipio (basically a county) of San Miguel de Allende, which includes the city proper and the rural "ranchos" in the outlying area. In the first 30 years of expatriate settlement, there was a flurry of charitable activity, and today there are over 200 charitable organizations in SMA. Some are based on basic needs, for instance Feed the Hungry is a program that raises money to feed school children two times a day for 10 and a half months a years (the school year). The Biblioteca Municipal (Public Library) is an amazing bilingual library that is one of the biggest in Mexico. There are fine arts organizations, educational scholarship associations, it goes on and on. Julia said that the part-timers are not as invested in the community as the full-time residents have been, and the charities have suffered as a result. There are fewer people to do the day-to-day work, although ironically, the community has become much wealthier with the infusion of ever wealthier gringos.

When is started off here, I thought my primary research objective (long-term) would be to examine the relationships between gringos and Mexicans. This division within the expatriate community is a new layer that I hadn't expected, and one that I plan to explore more fully during this research trip.

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

Lessons I've learned

As any of my students can confirm, I'm big on planning. When I go into the field, I make sure my equipment is working properly, I have extra batteries, and I always have back-up equipment. There is nothing more frustrating than finishing an interview that you thought was recorded, only to find out that (oh no) the tape recorder wasn't turned on or that the batteries went dead.

This type around, I decided to go high-tech. I bought a digital voice recorder. I love it, too. I bought a low-end (~$100 USD) Olympus D-2 that connects to my Mac via USB so I can download my audio files with no problem.

Until today.

I was in the middle of an outstanding interview with my neighbor, Julia (mentioned below). She's been here for over 2 decades, knows the history of San Miguel, and for years wrote the gossip column for Atención, the San Miguel bilingual newspaper. She has hours of stories, lots of free time, and can put me in contact with the most important old-timers (i.e., people who have lived here for 20+ years. In short, Julia is a folklorist's dream informant.

Until my digital recorder stopped working. I bought the D-2 because it has 18 hours of recording time. Yesterday I cleared the memory to be sure I'd be set to work with Julia today. About 45 minutes into the interivew, the recorder started beeping "memory almost full." I was only a few doors down from our house, so I apologized and excused myself from Julia's company and went home to download the files. When I did, however, the recorder kept telling me that the memory was full. I tried to delete another file I had missed. Then, the recorder just stopped working. It would turn on, show me the date and time, but would not record at all.

So, I went to plan B: using my MacBook and Soundstudio software to record the interview. Later tonight I found out that there is a bug in Soundstudio 3 (it keeps asking me to register and I've done that) and won't boot up. Discouraged, I walked back to Julia's to apologize and ask if we could reschedule. She was gracious, and quipped, "What, do you think I've got too many other things to do?" She is a wonderful person, very patient, and I can't wait to hear what else she has to say

But, my recorder is broken beyond repair (unless the Support Desk at Olympus can give me a hand via e-mail tomorrow). So, I'll head out to the Radio Shack (yes, they have those here) and see if another recorder is available. I've also reloaded Sound Studio, and it now appears to be working fine, so we'll see.

So much for planning ahead.

This type around, I decided to go high-tech. I bought a digital voice recorder. I love it, too. I bought a low-end (~$100 USD) Olympus D-2 that connects to my Mac via USB so I can download my audio files with no problem.

Until today.

I was in the middle of an outstanding interview with my neighbor, Julia (mentioned below). She's been here for over 2 decades, knows the history of San Miguel, and for years wrote the gossip column for Atención, the San Miguel bilingual newspaper. She has hours of stories, lots of free time, and can put me in contact with the most important old-timers (i.e., people who have lived here for 20+ years. In short, Julia is a folklorist's dream informant.

Until my digital recorder stopped working. I bought the D-2 because it has 18 hours of recording time. Yesterday I cleared the memory to be sure I'd be set to work with Julia today. About 45 minutes into the interivew, the recorder started beeping "memory almost full." I was only a few doors down from our house, so I apologized and excused myself from Julia's company and went home to download the files. When I did, however, the recorder kept telling me that the memory was full. I tried to delete another file I had missed. Then, the recorder just stopped working. It would turn on, show me the date and time, but would not record at all.

So, I went to plan B: using my MacBook and Soundstudio software to record the interview. Later tonight I found out that there is a bug in Soundstudio 3 (it keeps asking me to register and I've done that) and won't boot up. Discouraged, I walked back to Julia's to apologize and ask if we could reschedule. She was gracious, and quipped, "What, do you think I've got too many other things to do?" She is a wonderful person, very patient, and I can't wait to hear what else she has to say

But, my recorder is broken beyond repair (unless the Support Desk at Olympus can give me a hand via e-mail tomorrow). So, I'll head out to the Radio Shack (yes, they have those here) and see if another recorder is available. I've also reloaded Sound Studio, and it now appears to be working fine, so we'll see.

So much for planning ahead.

News from the Mushroom Capital

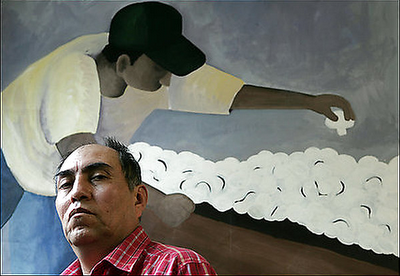

I'm blogging this article and photo from the Washington Post yesterday about Arturo Zavala, a man I met while I was doing fieldwork for my first book, Beyond the Borderlands. The article focuses on the fact that the new Homeland Security Agency is not prepared to handle the workload that would be involved with an amnesty program. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 provided amnesty and permanent residency for over 3 million people. Current legislation before the Senate would not provide an amnesty, but if any type of work visa is approved in the next year the agencies charged with processing the visas would not doubt be overwhelmed.

I'm blogging this article and photo from the Washington Post yesterday about Arturo Zavala, a man I met while I was doing fieldwork for my first book, Beyond the Borderlands. The article focuses on the fact that the new Homeland Security Agency is not prepared to handle the workload that would be involved with an amnesty program. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 provided amnesty and permanent residency for over 3 million people. Current legislation before the Senate would not provide an amnesty, but if any type of work visa is approved in the next year the agencies charged with processing the visas would not doubt be overwhelmed.Enter Mr. Zavala, who was legalized under the IRCA. His story is typical of many of the hongeros (mushroom pickers) in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania (a.k.a., the Mushroom Capital).

He waited years before his wife and children were able to join him in the U.S., and essentially missed the better part of his children growing up and family life in general. Mr. Zavala is a known to be a hard worker, good citizen, and an asset to his community. Making people like Arturo Zavala part of our nation, even with the potential backlog, seems well worth the effort.

Meet the neighbors

This morning I walked down my garden path and bumped into my neighbor who I'll refer to here as Julia. Julia is 92 years old and has lived in SMA for over 20 years. Her late husband was a journalist in NYC; he passed away 4 years ago.

I was apprehensive about approaching Julia for an interview. Several people I've met here refer to her as the "grand dame" of SMA. As I've alluded to here before, some of the not so "grand" dames of SMA are not very friendly or helpful (thus my reluctance to approach Julia). It turns out, Julia is worthy of her title. She has a sharp mind and incredible memory. She's also extremely well connected in SMA, and even offered to introduce me to a woman who has been here since the 1930s (I'm assuming she came here as a child). In any case, Julia may turn out to be one of those "key" informants that drives a project like this forward. When I told Julia I'd like to interview here, but didn't want to bother her if she was busy she replied, "Don't be silly. I love to be bothered."

I was apprehensive about approaching Julia for an interview. Several people I've met here refer to her as the "grand dame" of SMA. As I've alluded to here before, some of the not so "grand" dames of SMA are not very friendly or helpful (thus my reluctance to approach Julia). It turns out, Julia is worthy of her title. She has a sharp mind and incredible memory. She's also extremely well connected in SMA, and even offered to introduce me to a woman who has been here since the 1930s (I'm assuming she came here as a child). In any case, Julia may turn out to be one of those "key" informants that drives a project like this forward. When I told Julia I'd like to interview here, but didn't want to bother her if she was busy she replied, "Don't be silly. I love to be bothered."

Immigration Reform (the details)

Perusing the WP online just now I see that Kay Bailey Hutchinson and Mike Pence have posted the details of their proposed bill. Reading through this, the visa section is actually fairly well thought out and actually seems workable. The border enforcement sections are notably thin, not well thought out and, if our past experience is any indicator of future performance, not achievable.

Escort "home"

This article from the Washington Post today highlights one of the rarely discussed aspects of undocumented immigration: that once you're in the U.S., you are very unlikely to be apprehended and deported. As the article points out, it is only when these men and women make themselves known to the authorities, usually after the committ a crime, that they are at risk of being kicked out of the country. This suggests that, at least on one level, the system already has a means to separate out those who want to work from those who want to committ crimes.

Immigration Reform

I've been reading the very few immigration articles that have been published in the last week in the Washington Post, L.A. Times and NY times. There is little news out there, as the Middle East situation has rightly taken the front pages, but I plan to start posting the more significant articles here today.

The first is the new bill proposed by Kay Baily Hutchinson (R-TX) and Mike Pence (R-IN). It's a compromise that would allow the some 11 million undocumented stay in the U.S., but only after it is "certified" that the border is secure. In other words, this bill would do nothing, because the border can never be certifiably secure, thus the illegals would never receive documentation. The only thing certifiable about this proposal that puts border enforcement before addressing the real problem: allowing people into the country legally to do the jobs that no one currrently in the U.S. wants to do.

The first is the new bill proposed by Kay Baily Hutchinson (R-TX) and Mike Pence (R-IN). It's a compromise that would allow the some 11 million undocumented stay in the U.S., but only after it is "certified" that the border is secure. In other words, this bill would do nothing, because the border can never be certifiably secure, thus the illegals would never receive documentation. The only thing certifiable about this proposal that puts border enforcement before addressing the real problem: allowing people into the country legally to do the jobs that no one currrently in the U.S. wants to do.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Photo blog

We've had rain here the last four days. These photos were taken before the clouds rolled in on July 21.

San Miguel from the barrio Los Balcones. It's climb to get up here, but the view is worth it.

San Miguel from the barrio Los Balcones. It's climb to get up here, but the view is worth it.

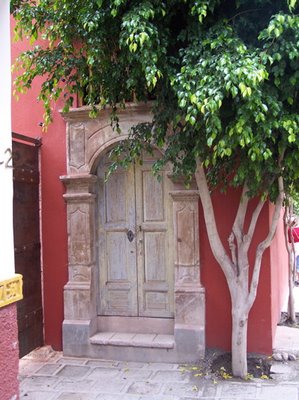

I've never seen so many wood doors in any other place in Mexico. We stumbled across this, and many others, taking a new route home from the jardín.

I've never seen so many wood doors in any other place in Mexico. We stumbled across this, and many others, taking a new route home from the jardín.

The famed Ignacio de Allende, for whom the pueblo of San Miguel also became "de Allende"

The famed Ignacio de Allende, for whom the pueblo of San Miguel also became "de Allende"

Ken and walked this path the first time we visited here. This meandering stone path is the center "street for a number of lovely homes.

San Miguel from the barrio Los Balcones. It's climb to get up here, but the view is worth it.

San Miguel from the barrio Los Balcones. It's climb to get up here, but the view is worth it. I've never seen so many wood doors in any other place in Mexico. We stumbled across this, and many others, taking a new route home from the jardín.

I've never seen so many wood doors in any other place in Mexico. We stumbled across this, and many others, taking a new route home from the jardín. The famed Ignacio de Allende, for whom the pueblo of San Miguel also became "de Allende"

The famed Ignacio de Allende, for whom the pueblo of San Miguel also became "de Allende"

Ken and walked this path the first time we visited here. This meandering stone path is the center "street for a number of lovely homes.

Reinvent yourself in Mexico

Aftre a few days of chatting up strangers in the jardín, I've had a great day in the field. I had two great interviews today and got stood up for the third (which is part of the game). Nevertheless, I've learned a great deal today, and I'm starting to see some trends in the information I'm collecting.

Aftre a few days of chatting up strangers in the jardín, I've had a great day in the field. I had two great interviews today and got stood up for the third (which is part of the game). Nevertheless, I've learned a great deal today, and I'm starting to see some trends in the information I'm collecting.One of the more interested things that I've been told, especially by women, is that moving to Mexico is a means of reinventing yourself. It appears that moving to a different country where no one may know you and your past gives these women freedom to be themselves in a way that was not possible living in the U.S. In otherwords, they say that moving to San Miguel has allowed them to be themselves completely on their own terms. The women that I've talked to so far have described themselves as people who were typically cautious and even fearful in the U.S., but once they came to Mexico, became more independent and adventurous in Mexico.

I find this curious, mainly because I've never been a big believer that a change in scenery can change who a person really is; for example, if you're lazy in one place moving to another won't transform you into a hardworker or stellar employee. But clearly these women see the move away from the U.S. and the obligations and expectations of society, their families, and (in many cases) the ex-husbands they left behind a means to express themselves in a way that they found impossible in the U.S.

I've also met a number of men and women who simply came to San Miguel, fell in love with the place, and then went home and sold off their worldly possessions and moved here. I haven't spent too much time in Paris or other places with well-known expatriate communities, but I would imagine that this would also the case there (or with any beautiful place). All told, there are a lot of people here who were really looking for a complete change of lifestyle or were burnt out on living in the U.S., and found the perfect place in San Miguel.

Saturday, July 22, 2006

I love my job, I hate my job

Nothing unusual about this, I know. Any job will have its ups and downs, doing ethnography is no different. What is different, however, is the emotional swings that are part of conducting ethnographic work. I remember the year before I went into the field my grad school colleague, Sara Davis, spent a year in China. When she got back she summed up her normal days something like this: she would go out in the morning, do an interview, then have to come home a take a nap.

At the time this seemed rather strange. Why would you need to nap after an interview?

Well, until you've done this type of research, you simply cannot comprehend the level of energy it takes to get through a working day. Okay, I'm going to try to describe it, but don't be surprised if you don't "get it." Some things in life have to be experienced.

The most important issue is that being in the field means you're always "on." Teaching a class is the closest approximation of what this is like. When you're teaching, for the entire class period you're on stage. You have the (hopefully) undivided attention of 30+ people who are looking to you to lead the discussion, set the tone and pace of the session, and generally keep things moving. If you screw up, people will notice.

Fieldwork is a lot like teaching a class that never ends, or lasts all day long. The entire time you're in the field you have to be "on" meeting people, almost always strangers. You have to make a favorable first impression on the people you meet, and if they meet your research criteria, hopefully they will want to assist you with your project. First impressions here are essential, probably more important than in everyday interactions so you can get the information you need. You have to be friendly and to establish both trust and rapport with anyone who might be a potential informant (or know a potential informant). This means you'll have to effectively describe who you are, what you hope to accomplish with your project, and most importantly, why you think they should share their life stories and experiences.

Even when you're not "working" officially, people will be watching. Your character will be observed and if you screw up, that could tank a project before it even begins (more on this later)

In order to find informants in San Miguel de Allende (SMA), I started by putting posts on internet chat rooms and discussion boards for Americans and Canadians who live in Mexico. This yielded some great contacts. My first interview was with a gentleman who has lived here for 2 years. He suggested that I try to meet people in the jardín (central plaza). For the last three days I've been in the jardín at various times of the day striking up conversations with people who look like gringos. You can never tell whether the person you're talking to lives here or is just visiting, and I've started more than a few conversations with tourists, or even "regulars," tourists who come back every year or six months, but still don't live here. They've given me some good information, but I can't use them for the oral history component of this project.

This means that I can spend hours talking to people and may not find someone who has information that is useful to my project. Even if I find someone who apparently "fits" the criteria for your project, they may not want to talk to me. Or they want to talk to me, but only under certain conditions. For instance, I met a man yesterday who was specifically looking for a pay back for his time (that is, he wanted me to pay for his time), something that I cannot and will not be able to give. So, you have to convince these potential informants that their contribution to general knowledge (a.k.a. the greater good) is a worthy of their time and effort. I've also met a fair number of men who are looking for hook-ups, so of course they're immediately knocked off the list.

The point I want to make here is that everytime I step out the door and start to talk to people, it's stressful and exhausting. It's not unusual for me to come home in the afternoon for comida (the big meal of the day, taken around 2 PM) and need a nap. Couple the ongoing stress of always being "on" with the altitude here (about 6435 feet) and that this city set on a large hill (which means the first week I felt as if I were hiking, not walking) and that, on average, I'm walking between 8 and 10 kilometers per day (according to my pedometer). When the day ends, I'm beat.

One last point: although being in Mexico is great, doing fieldwork here is no vacation. Sure, I'm surrounded by a lovely colonial city, but I rarely have time to enjoy most of what is around me because I'm working. When I get back to the states, I'll need a vacation to prepare for my other job teaching at George Mason University.

I love Mexico, and I love working here. But there are moments when I hate it, too. This is all part of the ups and downs of doing ethnography.

At the time this seemed rather strange. Why would you need to nap after an interview?

Well, until you've done this type of research, you simply cannot comprehend the level of energy it takes to get through a working day. Okay, I'm going to try to describe it, but don't be surprised if you don't "get it." Some things in life have to be experienced.

The most important issue is that being in the field means you're always "on." Teaching a class is the closest approximation of what this is like. When you're teaching, for the entire class period you're on stage. You have the (hopefully) undivided attention of 30+ people who are looking to you to lead the discussion, set the tone and pace of the session, and generally keep things moving. If you screw up, people will notice.

Fieldwork is a lot like teaching a class that never ends, or lasts all day long. The entire time you're in the field you have to be "on" meeting people, almost always strangers. You have to make a favorable first impression on the people you meet, and if they meet your research criteria, hopefully they will want to assist you with your project. First impressions here are essential, probably more important than in everyday interactions so you can get the information you need. You have to be friendly and to establish both trust and rapport with anyone who might be a potential informant (or know a potential informant). This means you'll have to effectively describe who you are, what you hope to accomplish with your project, and most importantly, why you think they should share their life stories and experiences.

Even when you're not "working" officially, people will be watching. Your character will be observed and if you screw up, that could tank a project before it even begins (more on this later)

In order to find informants in San Miguel de Allende (SMA), I started by putting posts on internet chat rooms and discussion boards for Americans and Canadians who live in Mexico. This yielded some great contacts. My first interview was with a gentleman who has lived here for 2 years. He suggested that I try to meet people in the jardín (central plaza). For the last three days I've been in the jardín at various times of the day striking up conversations with people who look like gringos. You can never tell whether the person you're talking to lives here or is just visiting, and I've started more than a few conversations with tourists, or even "regulars," tourists who come back every year or six months, but still don't live here. They've given me some good information, but I can't use them for the oral history component of this project.

This means that I can spend hours talking to people and may not find someone who has information that is useful to my project. Even if I find someone who apparently "fits" the criteria for your project, they may not want to talk to me. Or they want to talk to me, but only under certain conditions. For instance, I met a man yesterday who was specifically looking for a pay back for his time (that is, he wanted me to pay for his time), something that I cannot and will not be able to give. So, you have to convince these potential informants that their contribution to general knowledge (a.k.a. the greater good) is a worthy of their time and effort. I've also met a fair number of men who are looking for hook-ups, so of course they're immediately knocked off the list.

The point I want to make here is that everytime I step out the door and start to talk to people, it's stressful and exhausting. It's not unusual for me to come home in the afternoon for comida (the big meal of the day, taken around 2 PM) and need a nap. Couple the ongoing stress of always being "on" with the altitude here (about 6435 feet) and that this city set on a large hill (which means the first week I felt as if I were hiking, not walking) and that, on average, I'm walking between 8 and 10 kilometers per day (according to my pedometer). When the day ends, I'm beat.

One last point: although being in Mexico is great, doing fieldwork here is no vacation. Sure, I'm surrounded by a lovely colonial city, but I rarely have time to enjoy most of what is around me because I'm working. When I get back to the states, I'll need a vacation to prepare for my other job teaching at George Mason University.

I love Mexico, and I love working here. But there are moments when I hate it, too. This is all part of the ups and downs of doing ethnography.

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Thanks Jack Black

One more thing of note from today: my son decided yesterday that he HAD to have a luchador mask. For those of you who have not seen Nacho Libre, Jack Black has popularized the world of Mexican wrestling for gringo kids. Hurrah! (that was intended to be a bit sarcastic). In any case, here is my little luchador. He has not picked a name yet.

The other side of San Miguel

This man walked in front of me as I snapped the photo. Note the flowers, fruit, streamers and piñatas behind him.

This man walked in front of me as I snapped the photo. Note the flowers, fruit, streamers and piñatas behind him. Well, I found it. This is the mercado, the wonderful place that sells mounds of interesting stuff: fresh produce, meat, cool piñatas, flowers, clothing and just about anything else you might desire. The Mercado Ignacio Ramirez is located at the top of one of San Miguel's hills. From the jardín (centro) it's impossible to see this. We walked up because my neighbor, a Canadian woman who vacations here for long periods (she's been here for 8 weeks this summer) told us that there was artisan'ssan market at the top of the hill. I assumed it would be full of artesanias (arts and crafts), which it did have, but it also had all of the other interesting things a Mexican mercado will have.

Well, I found it. This is the mercado, the wonderful place that sells mounds of interesting stuff: fresh produce, meat, cool piñatas, flowers, clothing and just about anything else you might desire. The Mercado Ignacio Ramirez is located at the top of one of San Miguel's hills. From the jardín (centro) it's impossible to see this. We walked up because my neighbor, a Canadian woman who vacations here for long periods (she's been here for 8 weeks this summer) told us that there was artisan'ssan market at the top of the hill. I assumed it would be full of artesanias (arts and crafts), which it did have, but it also had all of the other interesting things a Mexican mercado will have.Today the mercado was populated exclusively with Mexican patrons. On the street where it is located, there are also a number of great shops that we've been looking for: three great butcher shops and a place that sells roasted chicken (they are to die for). We also found a summer language school for the kids, so in all it was a successful morning.

This afternoon I had my first interview, and it went well. As I suspected from my encounters in the airport with other San Miguel residents, he was a fluid conversationalist and gave me a lot to think about. He suggested that I just "hang out' in the jardÃn in the mornings as a way to meet potential informants. The benches that face the parrochia (the town's parish church) are almost always taken by Gringos and other expatriates, and he said when he and his wife moved here they found it a good way to make friends. I'll give it a try tomorrow.

What kind of place is San Miguel?

This is a photo of the front of our Mexican home.

This is a photo of the front of our Mexican home.I collapsed last night after one of the most grueling days of my fieldwork. As has been our habit of late, we all set out early yesterday in search of several things: a summer camp for the kids, the public library (the alleged "center" of the expatriate community in SMA), and a decent fruteria and carnicería. I'm having a difficult time getting my head around this town. At first glance, it seems like a typical Mexican town, but then there are aspects of being here that make it very different from the other places in Guanajuato that I've worked in and visited.

First of all, as far as I can tell, there is no mercado, or large market where individuals sel meats, cheeses, fruits, prepared foods and other miscellaneouss items. This is very strange for me, as I've never found any Mexican town or neighborhood to be as inconvenient as San Miguel appears to be. First off, there are very few banks around town. In fact, I've only found two so far. In so many towns in western Mexico is it typical to find a bank on every corner in the center of town (i.e., lots of places to change money). It's also atypical not to have a big market, and not to have little tienditas in the neighborhood. Ken and I have walked nearly a half mile in every direction of our house looking, and we haven't found any "mom and pop" tienditas within a block or two of our house. We do have supermercado in the plaza next to our home. This is great, but the produce and meat leave much to be desired.

Like many other communities in this part of Mexico, our house is located in a lovely community that is surrounded by inconsistent development. This, for example, is a photo of the neighborhood right outside our own:

This appears to be another community under construction. But, it may be a project that's been abandoned (there hasn't been any activity there since we arrived). From my bedroom window, I can see my closest neighbors are living in small shanties. There is no consistent zoning here, but that doesn't seem to be a problem for property values, or people wanting to buy or rent here.

This appears to be another community under construction. But, it may be a project that's been abandoned (there hasn't been any activity there since we arrived). From my bedroom window, I can see my closest neighbors are living in small shanties. There is no consistent zoning here, but that doesn't seem to be a problem for property values, or people wanting to buy or rent here.The other major surprise is that many of the Americans who live here seem to be pretty young. I've set up an interview for later today with a couple who are in their early 50s. I have an appointment for early next week to interview another couple who have lived here for 5 years. They're in their mid-30s. I've seen a few older people,peoplee confined to wheelchairs, that appear to be in their 70s or perhaps older, but for the most part, the non-Mexicans I've bumped into here are younger than I would have expected for a "retiree." One thing of note, the younger couple I mentioned above bristle at the idea of being "retired." They prefer to say that they're "unemployed."

While there are plenty of McMansions and other extremely fine homes, there are a fair number of expatriates living in what I would delicately term "modest" housing, such as camper trailers and very small houses in need of lots of repair.

Last night, Ken struck up a conversation with our next-door neighbors: two Canadian sisters who are vacationing here with their children. They mentioned that their children were taking tennis lessons nearby, and that we might want to come with them to meet the tennis instructor and see about lessons for our kids (my daughter loves tennis). I really didn't want to go along, and would have preferredd to let Ken walk the kids up to meet the tennis pro. Ken was insistent that I go along, however, because as he said, "You never know what you're going to find here."

Boy, was he right. The tennis pro, it turns out, is the son of an American who came to SMA right after WW II and married a young Mexican woman. They settled permanently in San Miguel, had children and never left. His son now gives tennis lessons to Americans and others for extremely reasonable rates (my kids will have a lesson together for $12 USD per hour). He also has several apartments on his property in addition to his three pristine clay tennis courts. He raises fighting cocks, stores vehicless for people who need a place to garage their cars in San Miguel, and has plans to open an RV park on his property in the near future. This man I'll refer to as "David" is in many respects part of the puzzle of San Miguel: he is truly Mexican, but very connected to the American community here. He speaks English and Spanish, and has many American and Mexican friends. The tennis pro, in other words, was not the country club guy that I expected. He was a more typical Mexican man who, like many of his fellows throughout the republic, is making a living using the tools he has available to him.

"David" is emblematic of what I will refer to as the puzzle of SMA, the unique cultural hybrid that is not easily defined.

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

Intro Redux

I wrote the post below a few months back, well before this project got off the ground. For those of you who have written wondering what I'm doing in San Miguel, here is the overview:

The Gringa in San Miguel: Introductions: Why a research blog?

The Gringa in San Miguel: Introductions: Why a research blog?

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

It's been a while...

Okay, so it's been a long, long time since I started an ethnographic project. I've been in Mexico, and even here in San Miguel, every six months or so over the last 7 years. I thought that starting this project, in a city that I know fairly well, would be fairly straightforward. What I didn't expect is the feeling of being overwhelmed getting around the city.

When I've been here in the past, I usually take a hotel near the jardín. When you're in the center of town, you're in the center of everything, and bumping into Americans or Canadians (a.k.a. potential informants) is as easy as asking for information or simply striking up a conversation. I'm living a small colonia right next to the "zona centro," at most a mile from the jardín.

This morning Ken, the childen and I set off early to find our best route to el centro and to locate the camps where the childen will be spending their days while Ken and I work. As we walked, I quickly realized that this city's grid is not so much a grid but series of meandering streets that follow an approximate grid, but not quite. My hometown (Morgantown, WV) is actually quite similarly laid-out (over the face of a mountain). So we walked, got confused, turned around, hit a dead end (for construction) and then found that my son's camp location is not anywhere near where I had been told, but a long drive north of town (and for all my purposes, completely unfeasible). In two and a half hours we walked 4 miles (according to my pedometer) and got home grumpy and exhausted.

And I didn't talk to a single retiree.

I brought a copy of my old hard drive with me, and I started to peruse my fieldnotes from 1999. I came across an early entry where I noted that I had been in Textitlán for five days and hadn't gotten a single interview. Ah, how those (terrible) memories of being a new fieldworker came flooding back. It takes time, and although I'm a seasoned researcher, I need to give myself time: time to adjust to my new neighborhood, time to rest up after the hellacious trip yesterday, time to find the best routes through town, and time to find a taquería that makes outstanding tacos al pastor. Things will start to come together, but they won't be together today.

When I've been here in the past, I usually take a hotel near the jardín. When you're in the center of town, you're in the center of everything, and bumping into Americans or Canadians (a.k.a. potential informants) is as easy as asking for information or simply striking up a conversation. I'm living a small colonia right next to the "zona centro," at most a mile from the jardín.

This morning Ken, the childen and I set off early to find our best route to el centro and to locate the camps where the childen will be spending their days while Ken and I work. As we walked, I quickly realized that this city's grid is not so much a grid but series of meandering streets that follow an approximate grid, but not quite. My hometown (Morgantown, WV) is actually quite similarly laid-out (over the face of a mountain). So we walked, got confused, turned around, hit a dead end (for construction) and then found that my son's camp location is not anywhere near where I had been told, but a long drive north of town (and for all my purposes, completely unfeasible). In two and a half hours we walked 4 miles (according to my pedometer) and got home grumpy and exhausted.

And I didn't talk to a single retiree.

I brought a copy of my old hard drive with me, and I started to peruse my fieldnotes from 1999. I came across an early entry where I noted that I had been in Textitlán for five days and hadn't gotten a single interview. Ah, how those (terrible) memories of being a new fieldworker came flooding back. It takes time, and although I'm a seasoned researcher, I need to give myself time: time to adjust to my new neighborhood, time to rest up after the hellacious trip yesterday, time to find the best routes through town, and time to find a taquería that makes outstanding tacos al pastor. Things will start to come together, but they won't be together today.

Monday, July 17, 2006

The Gringa has Landed

We're arrived in San Miguel, exhausted but happy to be unpacking. I'll be back tomorrow with updates, photos, and more.

Saturday, July 15, 2006

Sane Immigration Policy

I've been away from the blog for the last 48 hours (packing), but I stumbled across an op-ed in the Washington Post that will appear tomorrow morning. The op-ed mentions three strategies for a workable immigration policy. For those of you who have had me in class over the years, what Tamar Jacoby proposes many of the same things you've heard me mention in the past.

The first is to raise our immigration quotas so that they match our labor needs. This is a simply "open market" strategy. Immigration flows should match U.S. labor needs. Few people will risk their lives to come to the U.S. if they know there is little labor demand (also, why come here to be unemployed?). Many of our undocumented residents fill vital labor needs in our industries. Since we need the workers, it doesn't make sense that anyone who can legitimately find a job should have to work without documentation.

The second and third are to increase border scrutiny and workplace enforcement. I'm not a big fan of our militarized border; I think the fence idea is a great way to waste tax dollars. BUT, if the border security was focused on people who can actually hurt U.S. interests, such as drug runners, then I'm all for protecting the border. Think about how little illegal border traffic we would have, not to mention the revenue we could collect, if we decided to sell work visas. Then we would know that the people trying to cross the borders were doing something potentially harmful, and not trying to get into the country to do the work no one else wants to do.

I believe workplace enforcement can also work effectively. Our laws have never been set up to go after employers who break the law, something that is rarely discussed in our current immigration debate. This dual approach could yield amazing changes, and perhaps for once we could see the changes we actually intended.

Jacoby does not mention the "path to citizenship" that is so often touted by the Senate's version of the bill, which is an interesting omission. It is important that we offer people who have spent their entire lives here a means to formally join American society. I also think we could use another dual approach here as well: a path to citizenship for those who have been here and want to take that route, and a temporary work visa for those looking for short-term employment. I know many people in Mexico who don't want to live here, but they wouldn't mind coming here for two or three years to work for a while so they can save money to build a house, send their kids to college, or start a business in Mexico. This is an important option because it is not a good idea to force people onto a path to citizenship if they only want or need temporary work. A multifaceted approach to immigration will allow us to craft legislation that meets the nation's labor requirements, but also humanely addresses the needs of the men and women who fill those jobs.

The first is to raise our immigration quotas so that they match our labor needs. This is a simply "open market" strategy. Immigration flows should match U.S. labor needs. Few people will risk their lives to come to the U.S. if they know there is little labor demand (also, why come here to be unemployed?). Many of our undocumented residents fill vital labor needs in our industries. Since we need the workers, it doesn't make sense that anyone who can legitimately find a job should have to work without documentation.

The second and third are to increase border scrutiny and workplace enforcement. I'm not a big fan of our militarized border; I think the fence idea is a great way to waste tax dollars. BUT, if the border security was focused on people who can actually hurt U.S. interests, such as drug runners, then I'm all for protecting the border. Think about how little illegal border traffic we would have, not to mention the revenue we could collect, if we decided to sell work visas. Then we would know that the people trying to cross the borders were doing something potentially harmful, and not trying to get into the country to do the work no one else wants to do.

I believe workplace enforcement can also work effectively. Our laws have never been set up to go after employers who break the law, something that is rarely discussed in our current immigration debate. This dual approach could yield amazing changes, and perhaps for once we could see the changes we actually intended.

Jacoby does not mention the "path to citizenship" that is so often touted by the Senate's version of the bill, which is an interesting omission. It is important that we offer people who have spent their entire lives here a means to formally join American society. I also think we could use another dual approach here as well: a path to citizenship for those who have been here and want to take that route, and a temporary work visa for those looking for short-term employment. I know many people in Mexico who don't want to live here, but they wouldn't mind coming here for two or three years to work for a while so they can save money to build a house, send their kids to college, or start a business in Mexico. This is an important option because it is not a good idea to force people onto a path to citizenship if they only want or need temporary work. A multifaceted approach to immigration will allow us to craft legislation that meets the nation's labor requirements, but also humanely addresses the needs of the men and women who fill those jobs.

Thursday, July 13, 2006

Down to the wire

Dear Readers:

I'm in the midst of packing and trying to get everything at work in order for the trip. I will be posting, but more sporadically until we get to San Miguel. I will start posting daily from the field on Tuesday July 18.

Hasta pronto,

Deb

I'm in the midst of packing and trying to get everything at work in order for the trip. I will be posting, but more sporadically until we get to San Miguel. I will start posting daily from the field on Tuesday July 18.

Hasta pronto,

Deb

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Working from Home

I have less than a week to go before we depart. At the moment I'm frantic trying to get projects done that will be due while I'm gone. I'm also packing, which is best done over the period of a week (you're less likely to forget something).

San Miguel is a unique fieldsite in that there is a great deal of web information about the town and day-to-day life. My husband, Ken, stumbled across a great website yesterday: What's New and Exciting in San Miguel de Allende. The site is a portal for local news, events, and activities that are geared toward non-Mexican residents or visitors. There is also a great map of the city, which (believe it or not) has been hard to come by when I've been to San Miguel in the past. Because it is a tourist destination, the local maps are glossy tourist maps, not unlike those of Disney World. They're fine if you want to navigate the tourist area, but if you need a comprehensive map of the city, they won't work. The map I've linked above has a zoom-in feature that allows me to look at the city in small chunks, and allows me to become familiar with the street layout now. I'm not a map nut, but I find that if I spend some quality time studying maps before I get out on the street I get a feel of the place much more quickly.

This particular website, which is apparently operated by American expatriate, also gives a feel for the community as well as some of the local expat priorities and the places where people come together. Based on what I see here, and what I've read elsewhere, the library is cultural center. In addition to setting up appointments will the lovely people who have already contacted me, I plan to head to the library and several other key places mentioned on the site as a means of introducing myself to the community.

San Miguel is a unique fieldsite in that there is a great deal of web information about the town and day-to-day life. My husband, Ken, stumbled across a great website yesterday: What's New and Exciting in San Miguel de Allende. The site is a portal for local news, events, and activities that are geared toward non-Mexican residents or visitors. There is also a great map of the city, which (believe it or not) has been hard to come by when I've been to San Miguel in the past. Because it is a tourist destination, the local maps are glossy tourist maps, not unlike those of Disney World. They're fine if you want to navigate the tourist area, but if you need a comprehensive map of the city, they won't work. The map I've linked above has a zoom-in feature that allows me to look at the city in small chunks, and allows me to become familiar with the street layout now. I'm not a map nut, but I find that if I spend some quality time studying maps before I get out on the street I get a feel of the place much more quickly.

This particular website, which is apparently operated by American expatriate, also gives a feel for the community as well as some of the local expat priorities and the places where people come together. Based on what I see here, and what I've read elsewhere, the library is cultural center. In addition to setting up appointments will the lovely people who have already contacted me, I plan to head to the library and several other key places mentioned on the site as a means of introducing myself to the community.

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

Fieldwork and Risk (Serial rapist apprehended in San Miguel)

One of the fieldwork issues that is rarely discussed in graduate school is the personal danger a fieldworker might engage in the process of completing her work. When ethnographers take to the field, it is generally in a spirit of openness and trust. I spent 3 months going door-to-door in Mexico during my first field visit, and for the most part I felt completely safe. Only once did I have a creepy encounter, but looking back it was also pretty funny. I was interviewing an older woman about her family's immigration experiences when one of her adult sons returned home completely inebriated. He was fine at first, but then sat next to me on the sofa. Then he started to move closer, and closer, asking slurred questions like, "Perhaps the señorita would like a soda? or to stay for comida?" Finally, two of his brothers and his mother pulled him away from me apologizing profusely as I slipped out the door. Luckily I had finished most of the interview before he got home, so I didn't have to go back to the house later.

Every town is different, and while most of the places in Mexico I've visited and worked are much safer than the average American community (Mexico City being the exception), I still take precautions when I'm in the field. When my husband can't be in Mexico with me, which is often, I generally hire a Mexican assistant to accompany me during my work. This is particularly helpful in the winter months; otherwise, I wouldn't be able to work after dark.

Earlier this year I learned that there was a serial rapist in San Miguel, and that he targeted American women. I first heard the story on NPR. It was not comforting to know a serial rapist might be out there while I was walking around town looking for people to talk to (all of whom would be strangers). It was good news for me, and the people of San Miguel, that this man is now apparently off the streets. The report in El Universal.com.mx states that a suspect was apprehended, he confessed, and his DNA matches that of his victims.

Of course, given the size of San Miguel, the chances are good that there are other dangerous people around. To avoid potential problems, I follow the same common sense approach to working in communities in the U.S. For instance, I never do first interviews in the homes of my informants unless I am certain we won't be alone. I usually find a good coffee shop or quiet restaurant and set up shop in a quiet corner.

Every town is different, and while most of the places in Mexico I've visited and worked are much safer than the average American community (Mexico City being the exception), I still take precautions when I'm in the field. When my husband can't be in Mexico with me, which is often, I generally hire a Mexican assistant to accompany me during my work. This is particularly helpful in the winter months; otherwise, I wouldn't be able to work after dark.

Earlier this year I learned that there was a serial rapist in San Miguel, and that he targeted American women. I first heard the story on NPR. It was not comforting to know a serial rapist might be out there while I was walking around town looking for people to talk to (all of whom would be strangers). It was good news for me, and the people of San Miguel, that this man is now apparently off the streets. The report in El Universal.com.mx states that a suspect was apprehended, he confessed, and his DNA matches that of his victims.

Of course, given the size of San Miguel, the chances are good that there are other dangerous people around. To avoid potential problems, I follow the same common sense approach to working in communities in the U.S. For instance, I never do first interviews in the homes of my informants unless I am certain we won't be alone. I usually find a good coffee shop or quiet restaurant and set up shop in a quiet corner.

Monday, July 10, 2006

Fences don't make good neighbors

Los Angeles Times 10 July 2006

The billboard photographed here is located in Atlanta, home of a large and growing Mexican population. It's hard to imagine this type of public display fostering any type of neighborly relations between the Mexicans who have settled permanently Atlanta and their U.S.-born neighbors.

As the senate continues to debate immigration reform, on Monday afternoon the hearings finally shifted from discussions of faceless masses to the experiences of real Americans. As he recalled the experiences of his immigrant family, General Peter Pace broke down during his testimony. Nearly everyone present agreed that immigrants make wonderful contributions to our society. According to Washington Post, General Pace's comments moved several members of Congress. What effect his and other similar testimony will have in shaping immigration law is uncertain.

For too long we in the U.S. have thought of immigration as a one-way issue (i.e., they come here). Is it any less likely that Americans who retire in Mexico and Central America are "invaders," particularly in communities where their numbers are such that they could "take over" the communities where they live?

Regardless of how threatening one finds immigrant settlement, we still have to live together (let's face it, border fence or no, most of the immigrants who are here are planning to stay).

López-Obredor's challenge